Median Net Worth of White Families in California

- Introduction

- Wealth Is Disquisitional to Economical Security and Mobility, but Access Varies by Race and Ethnicity

- The Path to the Racial Wealth Gap

- Fundamental Factors Contributing to the Growing Wealth Split up

- Central Land Policies to Accost the Racial Wealth Gap

- The Future of Wealth

- Appendix

View the PDF version of this report.

Introduction

In the years since the 2007 Great Recession, economic commentary has veered between hailing the subsequent recovery and sounding the alarm about ascension inequality. Income inequality is often identified as a sign of both the state's underlying economic troubles and public policies that disproportionately do good the wealthy. An alternative indicator of the nation's social and economical health pertains to wealth, specifically the growing wealth gap amidst people of different races and ethnicities.[ane] This study illuminates the racial wealth gap, explores its underlying historical context, discusses some fundamental factors driving the wealth gap, and lays out a set of public policies that could put California and the nation as a whole on a better path to building wealth for millions of families.

Dorsum to Superlative

Wealth Is Critical to Economic Security and Mobility, but Admission Varies by Race and Ethnicity

Building wealth is a crucial cistron in promoting generational economic mobility and opportunity. Commonly measured in terms of net worth — the difference between gross assets and debt — wealth provides families with financial security. The greater a family'southward cyberspace worth, the more than resource they have to weather costly unexpected events, pay for higher education, accept risks on a business, purchase a home, and invest in other wealth-generating assets. Moreover, wealth can be transferred to the next generation through financial gifts or inheritances.

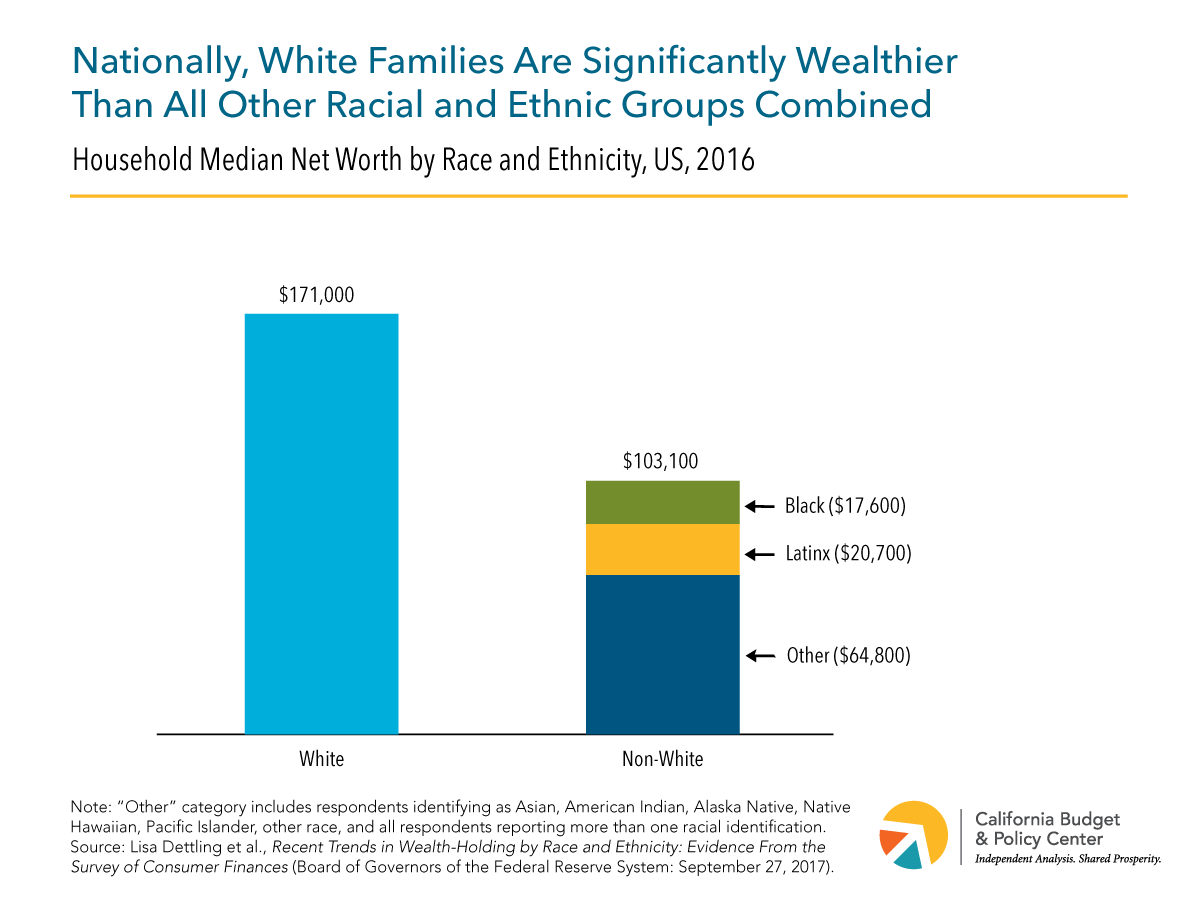

Income inequality has been extensively documented at both the country and national levels. Unfortunately, wealth inequality is fifty-fifty starker than income inequality. The top ane% of Americans took home 24% of all income, but they besides had 39% of all wealth in 2016.[2] However, wealth is not only inequitably distributed beyond the income spectrum. It is also unfairly allocated among people of different races and ethnicities. For example, in 2016, the typical — or median — white family's wealth nationally was $171,000 (Figure ane).[three] For black families, median wealth amounted to $17,600, or roughly 10% of that for white families. For Latinx families, median wealth was $twenty,700, or about 12% of that for white families. Put some other way, the typical white household has $9.72 in wealth for every $1 that a typical black family has and $viii.26 in wealth for every $i that a typical Latinx family has.

National data bear witness that this wealth disparity is non but explained by racial and indigenous differences in income. Though one might expect that those with greater income would also take greater wealth, the data indicate that this is non the example. In 2014, black households in the eye of the income distribution had $22,150 in median cyberspace wealth, far less than did whites in the second lowest twenty% of the distribution ($61,070) and just somewhat greater than that of whites in the bottom quintile ($18,361).[iv]

Data specific to the Los Angeles area highlights wealth inequality at the local level in California (Figure 2).[5] In 2014 in Los Angeles and Orange counties, US-built-in whites had a much college median household cyberspace worth ($355,000) than did most non-whites, including Latinx households ($46,000) and US-born blacks ($4,000). At the same fourth dimension, among non-white groups, Japanese ($592,000), Asian Indian ($460,000), and Chinese ($408,200) households had greater median internet worth than whites. The variation amidst Asian groups may reflect differing socioeconomic histories and migration patterns, and it echoes findings of substantial wealth inequality among Asian American communities in the Us.[6] These racial and ethnic differences reveal how some groups are amend positioned to make the kinds of critical investments in their futures that benefit their families and the broader community.

Weathering adverse events is more challenging for households that lack sufficient wealth. When families face financial setbacks such as chore loss or unexpected expenses, liquid assets — which tin can be converted easily to cash, such as coin in the depository financial institution — offering a needed fiscal cushion. Unfortunately, many black and Latinx families across the state do not accept plenty liquid wealth to absorb sudden shocks. Nationally, blacks in 2011 had only $25 in median liquid wealth, and Latinx residents had but $100.[7] In dissimilarity, the typical white family had $iii,000 in assets that they could quickly convert to cash if needed. In the Los Angeles area, the median value of liquid avails for white households in 2014 was $110,000, compared to $200 for Usa-born blacks, $0 and $7 for Mexican and not-Mexican Latinx households, respectively, $500 for Vietnamese, and $245,000 for Asian Indians.[8] Moreover, while the majority of American families own some wealth, besides many have nil or negative internet worth (indicating more debt than assets). This problem also varies by race and ethnicity, with far fewer white households nationally (9%) having no wealth in 2016 than did black (19%) or Latinx households (xiii%).[9]

Families with greater wealth are better positioned to exist able to transfer resources to family unit or friends. In add-on to having more than wealth, whites more often than not are improve able to rely on their social networks during hard times. In 2016, more than 7 in 10 white families expected that they could get $3,000 from friends or family unit during a financial emergency, with less than half of black and Latinx households reporting the same.[10]

These disparities are not a natural occurrence nor are they due to the individual failings of people of color. Rather, as the adjacent section points out, there are structural bug deeply rooted in our nation's long history of racism, which has infused every aspect of our economy and which our nation has failed to fully remedy.

Back to Top

The Path to the Racial Wealth Gap

Why Is There a Racial Wealth Divide?

The roots of the racial wealth divide can exist establish in racist policies and practices dating back to our nation'south early days. Under the institution of chattel slavery, enslaved Africans were valuable avails whose labor generated wealth for their white owners. After emancipation, blacks worked every bit landless tenant farmers and sharecroppers. They were besides largely close out of the Homestead Acts, through which the federal regime gave approximately 246 million acres to homesteaders — land that was the original source of family unit wealth for about ane-quarter of the United states of america adult population past 2004.[eleven]Public land acquisition and private land ownership were often explicitly restricted by race. White expansion west depended on the displacement of Native Americans from their territories and in many states — including California — country buying was limited to citizens, precisely to discriminate against non-whites ineligible for citizenship.[12]

In the period following the Great Depression and World War II, United states of america policy substantially restricted communities of color from benefiting from the wealth-edifice policies that helped grow the American heart course. Housing was a key area in which both public policy and individual deportment clearly advantaged whites. From 1934 to 1968, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) financed mortgages to expand homeownership, but also deliberately created segregated white neighborhoods to continue out "incompatible racial element[due south]."[xiii] Federal policies also harmed blackness neighborhoods by excluding many residents of these areas from eligibility for regime-backed loans and mortgages and discouraging lending to people of colour by designating their neighborhoods every bit bad credit risks. Nationally, due to the FHA'due south underwriting practices, just 2% of authorities-backed mortgages during this period (1934 to 1968) went to homebuyers of color.[14] These practices helped whites build avails, reduced home values in non-white neighborhoods, and pushed would-be homebuyers of colour into predatory land contracts that systematically stripped wealth from their communities.[15] While the Fair Housing Deed of 1968 banned racial discrimination in housing rentals and sales, it initially carried no real federal enforcement mechanism for discrimination claims, calorie-free penalties for violators, and high burdens for victims of bigotry.[xvi] Additionally, due to political resistance to desegregation, the Department of Housing and Urban Development oft avoided exercising or outright obstructed its legal mandate to affirmatively promote integration, thus entrenching these inequalities.[17] Today, housing discrimination remains a bulwark for people of color, who are recommended and shown fewer housing units than are equally qualified whites.[18]

The Racial Wealth Gap Has Widened in Contempo Decades

Due to a long history of bigotry, the racial wealth gap has been an ever-present feature of American economic life. Yet over the past several decades, this disparity has worsened. Although black and Latinx households saw their cyberspace worth rise incrementally, albeit fitfully, from 1983 to 2007, the net worth of white households was still steadily outpacing these gains.[19] Unfortunately, the Great Recession and the housing crisis reversed the gains fabricated past blackness and Latinx families, rolling back a generation's worth of progress.

The recession hitting Americans hard; from 2007 to 2010, median net worth for all racial and ethnic groups dropped by about 30%.[xx] Yet, for people of color, the pain did not end there. While white families' net worth stabilized in the immediate aftermath of the downturn (2010 to 2013), black and Latinx families continued to see their wealth decline by an additional 20%.[21] Latinx and Asian American households were unduly hurt by the foreclosure crisis, every bit they were far more than likely to live in one of the 5 states that were hardest hit, including California.[22] Though median net worth has since risen for all groups, the racial wealth split has connected to increase. From 2013 to 2016, median net worth for Latinx and black families rose 30% to 50%, respectively, compared to an increment of 17% for white families.[23] Despite these gains, the white-blackness wealth gap still increased by 16% and the white-Latinx gap rose by 14% during the aforementioned period.

Exacerbating the racial wealth divide is the nation's current wealth-building incentive structure. The federal government subsidizes savings and investment through sure tax benefits — including tax credits, deductions, exclusions, and preferential rates — which do not prove up on the federal government's residue canvass simply still count as public spending.[24] These subsidies perpetuate inequality by favoring those who are already wealthy, with the height twenty% of earners receiving most of the benefits.[25] With the exception of taxation credits, these revenue enhancement breaks are more probable to benefit white households, which disproportionately belong to the top xx%.

Merely every bit wealth is distributed unevenly, so are practices that strip wealth from communities. In the years leading up to the foreclosure crisis, predatory lenders made subprime mortgage loans — which have higher interest rates, fees, and penalties — irrespective of borrowers' power to repay. People of color, especially women, were particularly targeted past subprime lenders for bad mortgages even when they qualified for better loans, with blackness, Latinx, and Asian Pacific Islander women more likely to receive subprime mortgages than whites.[26] When the mortgage market crashed, these households lost substantial wealth. Payday lenders, which offering short-term, high-price loans with excessive interest rates that borrowers must repay quickly, nowadays another obstacle to wealth-edifice for communities of color.[27] Lenders tend to be full-bodied in neighborhoods of colour, and 60% of borrowers are women, particularly Latinx and blackness women.[28] These borrowers are oft living paycheck to paycheck and employ these loans to cover basic needs. They can become trapped by debt, taking out new loans with increasing fees to pay the previous loan. As a effect of this "loan churn," merely 14% of borrowers tin can repay their loans inside the brusk-term window and half of all loans are extended over 10 times.[29] In California, 83% of the total payday loan transactions in 2016 were for subsequent transactions by the same borrower and 79% of these subsequent loans were fabricated within a week of the previous loan, the majority on the same day.[xxx]

Back to Top

Key Factors Contributing to the Growing Wealth Carve up

Many factors are driving the growth of the racial wealth gap. This section examines three cardinal causes: housing, unemployment and the labor marketplace, and higher didactics.[31]

Unequal Access to Homeownership and Affordable Housing

Throughout the Us equally well equally in California, housing has become unaffordable for many families, whether they ain or rent their homes. In 2015, more than than 4 in x California households had unaffordable housing costs, meaning these costs exceeded 30% of household income.[32] More 1 in 5 households statewide faced astringent housing cost burdens, spending more than half of their income on housing. This affordability crisis predominantly affects Californians of color. Among all of the state's renters paying more than 30% of their income toward hire, more than ii-thirds (68%) were people of color and nearly half (46%) were Latinx.[33]

For those who own their homes, a firm is oftentimes a family's greatest investment, and it represents the largest single segment of their wealth portfolio. Among all homeowners, housing comprised nearly thirty% to 40% of their assets in 2016.[34] Historically less able to access homeownership, black and Latinx Americans have lower homeownership rates than whites. Nationally, more than than 7 in 10 white households (73%) ain their homes, compared to less than half of Latinx and black households.[35] In California, where homeownership rates are lower than the national average, more than 6 in 10 whites (63%) own their homes, while only one-third of blacks and about iv in 10 Latinx Californians (42%) are homeowners (Figure 3).[36] In Los Angeles and Orange counties specifically, over two-thirds of whites were homeowners in 2014, which was significantly greater than the homeownership charge per unit for virtually other racial and indigenous groups.[37]

Racial disparities in housing wealth account for a substantial share of the wealth dissever. According to one study, the number of years a household endemic their dwelling house explained 27% of the growth in the racial wealth gap between blacks and whites from 1984 to 2009.[38] Whites are more likely to receive family assistance in making a down payment on a home and generate housing wealth years earlier than blackness and Latinx families. Fifty-fifty among homeowners, a substantial racial wealth gap exists: black and Latinx homeowners even so see lower returns to homeownership. In 2016, net housing wealth among homeowners was $215,800 for white families, compared to merely $94,400 for blacks and $129,800 for Latinx families.[39] Greater access to assistance from family means that white buyers are more than likely to be able to make a down payment earlier in their lives also every bit to brand more sizable downward payments, which leads to lower interest rates and lending costs.[40] Additionally, considering of the legacy of residential segregation, blacks tend to own homes in majority black neighborhoods, and these homes do not appreciate at the same charge per unit as those in largely white neighborhoods.[41]

Given these deep disparities, some researchers argue that in lodge to help people of color build housing wealth on par with whites, increasing both homeownership rates and returns is key.[42] If blackness and Latinx families endemic their homes at the aforementioned rates as whites, the wealth gap would decrease past 31% and 28%, respectively.[43] Separately, equalizing returns to homeownership would reduce the blackness-white wealth gap by 16% and the Latinx-white gap past 41%.

Higher Unemployment and Unequal Admission to Well-Paying Jobs With Benefits

Earned income and employer-provided benefits are an important source of economic security for many American households. Taken together, unemployment and household income explain near 30% of the growth in the white-black wealth gap.[44]

Beyond all levels of education, the unemployment rate for blacks is higher than for whites.[45] Equal rates of employment would non be enough to eliminate the racial wealth carve up, equally white families with an unemployed head of household possess five times the wealth of black families headed by a person who works full-time.[46] Clearly, people of color remain at a disadvantage in the labor market place even when they are employed. Furthermore, blackness and Latinx workers are less probable to hold higher-paying jobs that offer key benefits like retirement plans, wellness coverage, or paid leave, all of which are important for wealth-building.[47] This insecurity may bear on women of color to an fifty-fifty greater extent. They face a "larger wage gap, greater job segregation, higher rates of unemployment, and principal caregiving responsibility" than do white women.[48] Latinx and black women are less likely than white women to have employers who offering retirement plans, and women in general are more probable than men to work part-time or low-wage jobs that restrict access to wealth-building benefits.[49]

The Heavier Burden of Higher Didactics Costs

Having at least a higher degree is increasingly tied to greater economic security. Workers with a college degree accept college lifetime earnings than those with only a high school diploma and are more likely to exist stably employed in a job with benefits.[50] Californians with a bachelor's caste can await more than double the average annual earnings of those with only a high school diploma.[51] Increasing access to higher education is also beneficial for the country. Some enquiry suggests that the lifetime return to the state per graduate with a bachelor's degree is over $200,000.[52] Withal, state investments in public college pedagogy lag far below pre-recession levels.[53] Over the years, spending cuts take shifted the cost of college education from the state to students and their families through increased tuition and fees.

However not all families tin can support their children'south education equally. In 2013, whites were more than twice as probable equally blacks to receive financial assistance from their parents for higher education.[54] This disparity in financial support is not due to a difference in parents' supportiveness of their children'southward postsecondary teaching. Indeed, research indicates that black parents are more probable to spend a larger share of their resources on their children's educational activity.[55] Those blackness parents who back up their children financially have less wealth and income than white parents who provide no financial support. However, in general, black families but accept less wealth to leverage toward the cost of an education.

Families may consider fiscal help, but that assistance is not always available or sufficient. In California, low- and middle-income students plough to Cal Grants, which are the foundation of California'southward financial help programme.[56] Just sixteen% and 25% of very depression-income black and Latinx students in California, respectively, receive a Cal Grant award.[57] The vast majority of black and Latinx students who do receive land financial assist become the Cal Grant B access award, which is intended to aid depression-income students pay for basic expenses yet has not kept pace with the country'south rising housing costs.[58] The federal Pell Grant has also eroded in value, failing to proceed up with rise costs of college attendance.[59]

Disproportionately burdened by ascent tuition and fees, facing insufficient fiscal aid, and less able to rely on family resources, low-income students equally well as students of color are more than probable to face economic barriers to completing their degrees. These students frequently have to employ a range of coping strategies that impede their bookish progress, including enrolling part-fourth dimension, dropping courses, skipping semesters, or taking a chore to cover expenses.[60] They as well are more probable to take on debt to finance their education. Among all households, black families are more encumbered by student debt than are white families. Over half (54%) of all black households headed by those ages 25 to 40 have student debt, compared to 39% of their white counterparts.[61] For Latinx households, but over 1 in 5 (21%) take student debt, likely due to lower rates of higher attendance and attainment. Black borrowers too tend to owe more than white borrowers and both blackness and Latinx borrowers are more likely to take out riskier private loans.[62] This debt burden can be an obstruction to attaining a caste, as black and Latinx student borrowers are more likely to drop out.[63] As a result, they lack access to the relative labor market stability and asset-building opportunities that come with a higher caste.

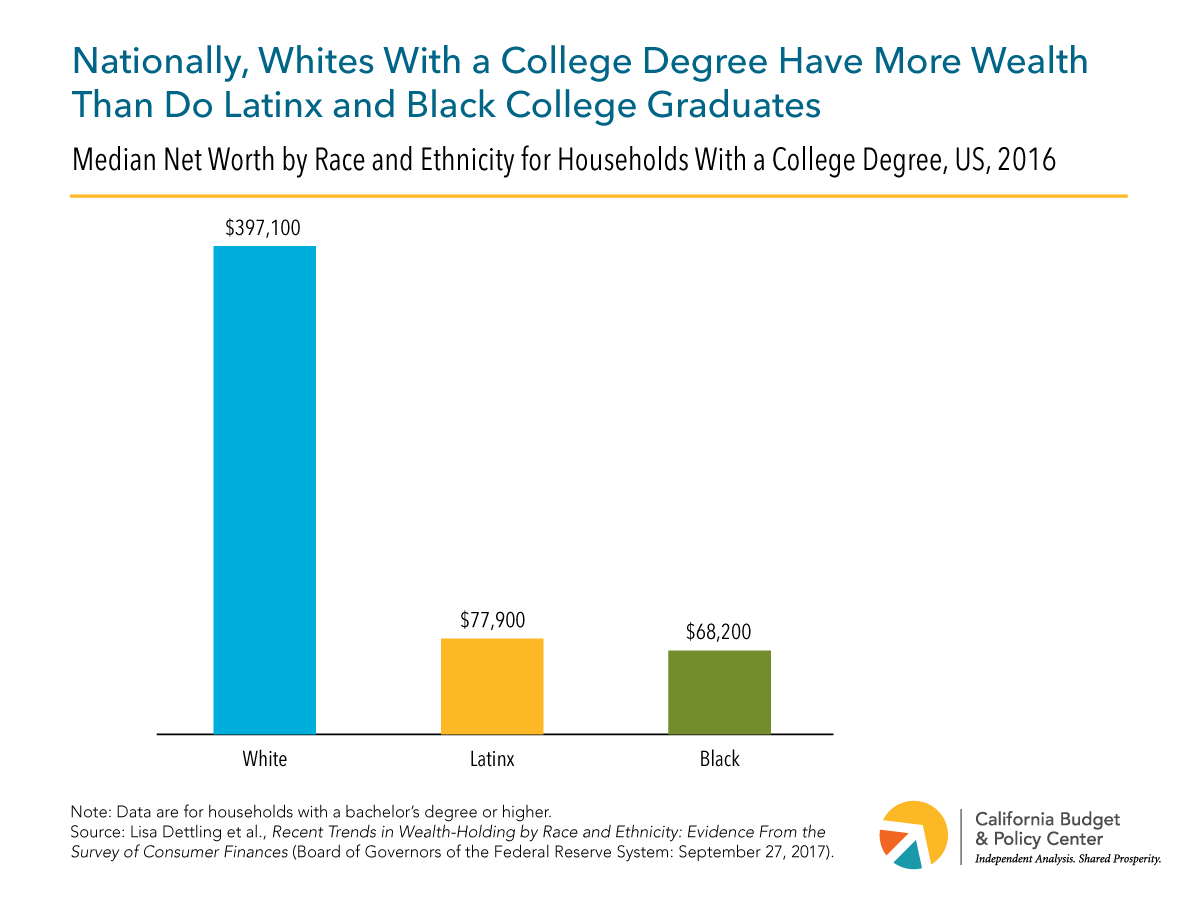

Still while higher education is associated with greater earning potential, boosting the number of black and Latinx students who attain a degree in and of itself will not eliminate the wealth divide. In role due to debt payments, higher take a chance of default, and disparate experiences in the labor market, black and Latinx graduates do not encounter returns to their education that are equal to those of their white peers. At every level of educational attainment, black and Latinx families have less median wealth than their white peers. Not merely do white college graduates concur more than than five times the wealth of black and Latinx graduates, simply even whites without a degree are wealthier (Figures four and 5).[64] Nor does the disparity disappear for those who received parental financial support for a degree, which is associated with degree completion but does niggling to reduce racial gaps in income or net worth.[65] In short, attaining a degree does not necessarily protect graduates of color from debt burdens or the discriminatory policies and practices that contribute to the racial wealth gap over the course of a lifetime.

Back to Top

Central State Policies to Address the Racial Wealth Gap

The inquiry on wealth overwhelmingly concludes that individual accomplishment is not sufficient to overcome growing racial and ethnic wealth inequalities. Given the important role of public policy in fostering both an American heart class and the racial wealth carve up, endmost the wealth gap will require a new approach to public policy at both the state and national levels. This section suggests some land-level policy changes that could increase wealth for communities of color and decrease the disparity between whites and other groups.

The Need for Action: Four Fundamental Policies to Build Wealth

1. Create a country-level manor tax

An manor tax is levied on large accumulations of wealth that are transferred from the estate of people who have died to their beneficiaries.[66] Ideally, the Usa would have a robust estate revenue enhancement that would reduce wealth accumulation, with the proceeds invested in wealth-building strategies designed to level the playing field for all Americans. However, the federal manor tax has been weakened dramatically since the late 1990s to the point that nearly all estates are exempt from this taxation.[67] Most recently, the Revenue enhancement Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 raised the exemption from the federal manor tax to more than than $x million per person.[68] This change will further concentrate wealth among families that are already highly advantaged. California should create its own manor tax, joining 18 other states and the District of Columbia that tax inherited wealth.[69] With such a tax, California could both reduce wealth disparities and employ the resulting revenues — potentially in the billions per yr — to fund wealth-building policies or other public investments that would benefit the vast bulk of Californians.[lxx]

ii. Support homeownership for low-income Californians

To ease the burdensome housing costs and help Californians build wealth, state policymakers tin can further assist low-income Californians become homeowners, which could benefit Californians of colour. One selection is to invest in shared equity programs, which offer subsidies to lower the initial costs of a home for new buyers.[71] When homeowners sell their home, a portion of the proceeds is reinvested in the programme, allowing future depression-income buyers to beget a home and keeping the program sustainable. California could significantly invest in affordable homeownership past providing funding for shared equity housing for those otherwise priced out of the housing market and tie funds to long-term affordability requirements. Local governments and nonprofits could be responsible for monitoring units and resales, and offering support to homeowners.

To help fund this investment, California should consider eliminating the state mortgage interest tax deduction. The deduction allows households to reduce their taxable incomes past the value of qualified mortgage interest expenses paid on upward to $1 one thousand thousand in debt and primarily benefits wealthy homeowners.[72] This revenue enhancement intermission exacerbates racial and ethnic disparities, with white families not merely more likely to own homes, only also to have more than valuable homes.[73] Eliminating the deduction would both make California's revenue enhancement code more than equitable and yield substantial acquirement for shared equity programs.[74]

three. Create debt-free public higher educational activity for low- and middle-income households

California policymakers should take steps to substantially deepen the state'south investment in higher educational activity, with a item focus on subsidizing the full cost of attendance for depression- and middle-income households. Targeting students with lower incomes would reduce the racial wealth carve up past eliminating borrowing for many students of color, thus removing i barrier to completion and increasing the return on a college degree by assuasive students to avoid wealth-stripping student debt.[75] To this end, policymakers should increase the supply of competitive Cal Grants and raise the value of the Cal Grant B admission award for living expenses.

four. Boost investments in children through Children'south Savings Accounts (CSAs).

CSAs are savings accounts for children that have the potential to reduce generational inequities in wealth-building. Seeded with an initial deposit from the state that would accrue interest throughout childhood, a CSA could be automatically opened for each child at nativity (with greater endowments for children from less wealthy families) or applied simply to children from depression-wealth households. Contributions from family and friends could receive a public match, the size of which could increase for families with less wealth. One time the kid reaches adulthood, the savings could be used for higher education, homeownership, or other investments throughout their lifetime. Such a program could essentially reduce the racial wealth gap and increase asset security.[76]

Back to Top

The Future of Wealth

The rise of a strong American middle class did not happen accidentally. Information technology required a good for you economy supported by big and intentional public investments. These deportment were largely structured to benefit whites to the exclusion of communities of colour, and that decision bears serious moral and economic consequences for our future well-existence. Nationally, whites are projected to become a racial minority past 2045.[77] In California, people of color already establish the majority of the state's population, and their share is projected to ascension to more than 2-thirds (68%) by 2045.[78] Every bit a upshot, the economic welfare of people of color will increasingly determine the welfare of our country and of the larger society. Californians and all Americans need to decide which futurity nosotros want. One option is to keep downward our current path, disproportionately concentrating wealth and opportunity with a handful of whites, while locking out people of color. A better option is to ameliorate public policies at the state and federal levels in order to ensure equitable investments in all of our people and create a strong and inclusive economy.

Back to Summit

Appendix

Measuring Wealth

Researchers primarily use iii surveys to explore the distribution of wealth in the Usa: the US Census Agency'due south Survey of Income and Plan Participation (SIPP), the Federal Reserve Lath's Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) conducted by University of Michigan faculty. While all iii of these surveys let for comparisons by race and ethnicity, these categories tend to be limited. For example, due to sample size constraints, Asians, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and those who report more than one race are grouped into a unmarried "Other" category, as in the SCF.[79] Wealth-related data by race and ethnicity is available for certain localities — including the Los Angeles area — from The National Asset Scorecard and Communities of Color survey (NASCC).[80] Due to these information limitations, The Racial Wealth Gap: What Nosotros Can Practise About a Long-Standing Obstacle to Shared Prosperity focuses on the national differences in wealth betwixt white, black, and Latinx households and reports local data when bachelor.

Back to Top

Endnotes

[1] In this report, the term "racial wealth gap" is used to refer to an economical trouble that affects various races and ethnicities.

[2] Jesse Bricker, et al., Changes in U.s. Family Finances From 2013 to 2016: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Lath of Governors of the Federal Reserve Arrangement: September 2017), p. ten.

[iii] Though these gaps subtract when accounting for other demographic and economic factors associated with wealth, sizable disparities remain. See Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Property past Race and Ethnicity: Prove From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[4] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Get Incorrect About Endmost the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Middle for Community Economic Development: April 2018), p. ix.

[5] Data are from the 2014 National Asset Scorecard and Communities of Color survey and are for Los Angeles and Orange counties. The authors exercise not account for nativity condition, with the exception of distinguishing between US-born blacks and African blacks. Median internet worth for African blacks was $72,000. See Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New Schoolhouse, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Eye for Community Economic Evolution: March 2016), p. forty.

[6] Christian East. Weller and Jeffrey Thompson, Wealth Inequality Amid Asian Americans Greater Than Amidst Whites (Center for American Progress: Dec 20, 2016).

[7] This assay excludes retirement savings. Including retirement savings, black and Latinx Americans had $200 and $340 in median liquid wealth, respectively, while whites had $23,000. Meet Rebecca Tippett, et al., Across Broke: Why Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Is a Priority for National Economic Security (Middle for Global Policy Solutions and Duke Enquiry Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at the Social Science Research Institute: May 2014), p. 2.

[eight] Data are from the 2014 National Nugget Scorecard and Communities of Color survey and are for Los Angeles and Orange counties. The authors do not account for nativity status, with the exception of distinguishing between Usa-built-in blacks and African blacks. See Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Knuckles University, The New School, the Academy of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Customs Economic Development: March 2016), p. 38.

[9] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding past Race and Ethnicity: Bear witness From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Lath of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[ten] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Arrangement: September 27, 2017).

[11] Thomas Chiliad. Shapiro, The Subconscious Price of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2004), p. 190.

[12] Office of the Historian, Usa Department of State, Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830; Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur, The Era of Reconstruction: 1861-1900 (National Park Service, United states Department of the Interior: 2017), p. 70; and Masao Suzuki, "Important or Impotent? Taking Some other Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law," The Periodical of Economical History 64 (2004), pp. 125-130.

[13] Richard Rothstein, The Racial Achievement Gap, Segregated Schools, and Segregated Neighborhoods: A Constitutional Insult (Economic Policy Found: November 12, 2014).

[xiv] Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, et al., The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Separate Is Hollowing Out America'due south Middle Form (Found for Policy Studies and Prosperity Now: September 2017), p. xv.

[fifteen] Jeremiah Battle, Jr., et al., Toxic Transactions: How Land Installment Contracts Once more Threaten Communities of Color (National Consumer Law Centre: July 2016), pp. three-4.

[16] Under the 1968 Fair Housing Human action, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had to investigate complaints of discrimination within xxx days. If HUD pursued the claim, it could simply seek voluntary settlements with noncompliant parties or propose complainants to file private lawsuits, for which penalties were capped at $ane,000. In 1988, Congress updated the Act to provide administrative enforcement of the law, extend HUD'due south investigation time to 100 days, and increase the maximum civil penalties, which currently range from $20,111 for a commencement offense to $100,554 for those with a history of offenses. See Douglas S. Massey, "The Legacy of the 1968 Fair Housing Act" Sociological Forum 30 (2015), pp. 571-588; Authoritative Conference of the Us, Enforcement Procedures Under the Off-white Housing Act (June 18, 1992); and 82 Federal Register 24523 (2017).

[17] Douglas S. Massey, "The Legacy of the 1968 Fair Housing Act" Sociological Forum 30 (2015), pp. 571-588; Nikole Hannah-Jones, "Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Ceremonious Rights Law," ProPublica (June 25, 2015).

[18] US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Housing Bigotry Confronting Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012: Executive Summary, (June 2013), p. 1.

[19] This assay excludes durable appurtenances. Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, et al., The Road to Cypher Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide Is Hollowing Out America's Middle Grade (Institute for Policy Studies and Prosperity At present: September 2017), p. 8.

[20] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Financesouth (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Organisation: September 27, 2017).

[21] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Belongings past Race and Ethnicity: Prove From the Survey of Consumer Financesouthward (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[22] Rebecca Tippett, et al., Beyond Broke: Why Closing the Racial Wealth Gap Is a Priority for National Economic Security (Center for Global Policy Solutions and Duke Research Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at the Social Science Research Institute: May 2014), p. 4.

[23] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Lath of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[24] Refundable revenue enhancement credits are the exception, every bit they are recorded in the federal budget. See Lewis Brown Jr. and Heather McCulloch, Building an Equitable Tax Code: A Primer for Advocates (PolicyLink: 2014), p. iii.

[25] Lewis Brown Jr. and Heather McCulloch, Building an Equitable Tax Code: A Primer for Advocates (PolicyLink: 2014), p. seven.

[26] Heather McCulloch, Endmost the Women'southward Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why Information technology Matters, and What Tin can Exist Washed About It (Closing the Women's Wealth Gap Initiative: updated Jan 2017), p. 9; Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street'southward Predatory Products Pillage Women's Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 16.

[27] Scott Graves and Alissa Anderson, Payday Loans: Taking the Pay Out of Payday (California Upkeep & Policy Center: September 2008), p. seven.

[28] Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street's Predatory Products Pillage Women's Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 18-19.

[29] Suparna Bhaskaran, Pinklining: How Wall Street's Predatory Products Pillage Women'south Wealth, Opportunities, and Futures (June 2016), p. 17.

[30] California Section of Business Oversight, Summary Report: California Deferred Deposit Transaction Law—Annual Written report and Industry Survey (May 31, 2017), p. 8.

[31] In a 2013 analysis, these areas explained 61% of the ongoing racial wealth divide between whites and blacks. See Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economical Divide (Establish on Avails and Social Policy: February 2013), pp. 2-3.

[32] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the Country Pay More Than They Tin Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Middle: September 2017).

[33] Sara Kimberlin, Californians in All Parts of the State Pay More Than They Can Afford for Housing (California Budget & Policy Center: September 2017).

[34] Lisa Dettling, et al., Contempo Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Lath of Governors of the Federal Reserve Organization: September 27, 2017).

[35] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[36] California Budget & Policy Heart analysis of U.s.a. Census Agency, American Community Survey data. Information are for household heads age 18 and older in 2016.

[37] Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke Academy, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economical Evolution: March 2016), p. 33.

[38] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Split (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: Feb 2013), p. 2.

[39] Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding past Race and Ethnicity: Show From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Lath of Governors of the Federal Reserve Arrangement: September 27, 2017).

[xl] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Separate (Institute on Avails and Social Policy: February 2013), p. three.

[41] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (Institute on Assets and Social Policy: February 2013), p. iii.

[42] Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Institute for Assets and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), p. 1.

[43] If black families owned their homes at the same rate every bit whites, the median black household's wealth would increase past over $32,000 (451%). For Latinx families, equalizing homeownership rates would increase the median household wealth by over $29,000 (350%). Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Institute for Avails and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), pp. 11-13.

[44] Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Blackness-White Economic Divide (Constitute on Assets and Social Policy: Feb 2013), pp. ii-iii.

[45] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Go Wrong Well-nigh Endmost the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Customs Economic Evolution: April 2018), p. seven.

[46] William Darity Jr., et al., What We Become Wrong About Endmost the Racial Wealth Gap (Samuel DuBois Cook Eye on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Evolution: April 2018), p. 8.

[47] Laura Sullivan, et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (Constitute for Assets and Social Policy and Demos: 2015), p. 25.

[48] Heather McCulloch, Closing the Women's Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why It Matters, and What Can Be Done About It (Closing the Women'southward Wealth Gap Initiative: updated January 2017), p. 7.

[49] The data refers specifically to defined contribution plans. See Heather McCulloch, Closing the Women's Wealth Gap: What It Is, Why Information technology Matters, and What Can Be Done About It (Endmost the Women'southward Wealth Gap Initiative: updated Jan 2017), p. 12.

[50] Tatjana Meschede, et al., "'Family Achievements'? How a College Degree Accumulates Wealth for Whites and Not for Blacks," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99 (2017), p. 123.

[51] Hans Johnson, Testimony: The Need for College Graduates in California'due south Hereafter Economy (The Public Policy Institute of California: Nov 1, 2017).

[52] Jon Stiles, Michael Hout, and Henry Brady, California's Economic Payoff: Investing in College Admission and Completion (The Entrada for College Opportunity: April 2012), p.13.

[53] Amy Rose, State Spending Per Student at CSU and UC Remains Well Beneath Pre-Recession Levels, Despite Contempo Increases (California Budget & Policy Center: March 2018).

[54] Yunju Nam, et al., Bootstraps Are for Black Kids: Race, Wealth, and the Bear on of Intergenerational Transfers on Adult Outcomes (Insight Centre for Community Economic Development: September 2015), p. 8.

[55] Tatjana Meschede, et al., "'Family Achievements?' How a Higher Degree Accumulates Wealth for Whites and Not for Blacks," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99 (2017), p. 124.

[56] There are three types of Cal Grant awards: Cal Grant A is used for tuition and fees; Cal Grant B provides an allowance for living costs known as an "admission honour" (in add-on to tuition and fee assistance afterward the starting time yr); and Cal Grant C is for students who nourish occupational or career colleges. Run into California Student Aid Committee, What Is a Cal Grant Award?

[57] Data are from 2008. See The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Latinos (Apr 2015), p. eighteen and The Campaign for College Opportunity, The State of Higher Education in California: Blacks (May 2015), p. 29.

[58] The Campaign for College Opportunity, The Country of Higher Education in California: Latinos (April 2015), p.xix; The Campaign for Higher Opportunity, The State of Higher Teaching in California: Blacks (May 2015), p. 29; and Amy Rose, Barriers to Higher Education Attainment: Students' Unmet Basic Needs (California Budget & Policy Eye: May 2018).

[59] Spiros Protopsaltis and Sharon Parrott, Pell Grants — a Fundamental Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity — Need Strengthening, Not Cuts (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: July 27, 2017).

[60] Amy Rose, Barriers to Higher Education Attainment: Students' Unmet Bones Needs (California Budget & Policy Center: May 2018).

[61] Mark Huelsman, et al., Less Debt, More than Equity: Lowering Pupil Debt While Closing the Black-White Wealth Gap (Demos and Institute on Assets and Social Policy: 2015), pp. 16-17.

[62] Latinx students tend to borrow smaller amounts than both blacks and whites at public institutions but may borrow greater amounts at individual for-profit institutions. Run into Mark Huelsman, The Debt Split: The Racial and Course Bias Behind the "New Normal" of Student Borrowing (Demos: May 19, 2015), pp. 7-viii.

[63] Marking Huelsman, The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias Behind the "New Normal" of Student Borrowing (Demos: May xix, 2015), pp. 14-16.

[64] For a white household whose head does not have a bachelor's degree, median internet worth is $98,100. For a black household whose head does have a higher caste, median net worth is $68,200. For Latinx households, the equivalent figure is $77,900. Run into Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Property by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Arrangement: September 27, 2017).

[65] Yunju Nam, et al., Bootstraps Are for Blackness Kids: Race, Wealth, and the Impact of Intergenerational Transfers on Adult Outcomes (The Insight Center for Community Economical Development: September 2015), p. 12.

[66] Jonathan Kaplan, Repeal of the Manor Tax Would Reduce Federal Resources While Key Public Services Are on the Chopping Block (California Budget & Policy Center: October 26, 2017).

[67] Even earlier the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which further scaled dorsum the national estate tax, only 2 out of every one,000 estates were subject to the revenue enhancement. Jonathan Kaplan, Repeal of the Estate Tax Would Reduce Federal Resources While Key Public Services Are on the Chopping Block (California Budget & Policy Heart: Oct 26, 2017).

[68] Steven Bliss and Chris Hoene, Final GOP Tax Plan Is a Big Souvenir to the Wealthy, only Would Harm Most Households and Our Economy (California Budget & Policy Heart: December 18, 2017).

[69] In gild to constitute a state manor tax, the Legislature would have to ask voters to repeal or meliorate Proposition half dozen of 1982, which prohibits the state from imposing an estate, inheritance, or wealth tax. See California Budget & Policy Center, Principles and Policy: A Guide to California's Tax System (Apr 2013), p. 21. For more information about state estate taxes, see Elizabeth McNichol, State Estate Taxes: A Central Tool for Broad Prosperity (Center on Upkeep and Policy Priorities: May 11, 2016).

[70] For estimates on the amount of acquirement an estate taxation could raise, see Elizabeth McNichol, Land Manor Taxes: A Fundamental Tool for Broad Prosperity (Center on Upkeep and Policy Priorities: May xi, 2016) and Legislative Annotator'due south Office, A.M. File No. 2017-038 (Nov 30, 2017).

[71] Brett Theodos, et al., Affordable Homeownership: An Evaluation of Shared Equity Programs (Urban Institute: March 2017), p. one.

[72] William Chen, Spending Through California's Tax Lawmaking (California Budget & Policy Center: August 2016).

[73] In 2016, the boilerplate net housing wealth in the U.s.a. was $215,800 for white homeowners versus $94,400 for blackness homeowners and $129,800 for Latinx homeowners. See Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[74] The Department of Finance estimates that California will lose $4 billion in revenue due to the mortgage interest deduction in state fiscal year 2018-nineteen. Come across California Department of Finance, Tax Expenditure Written report: 2018-19, p. 5.

[75] Mark Huelsman, et al., Less Debt, More Equity: Lowering Student Debt While Closing the Black-White Wealth Gap (Demos and Institute on Avails and Social Policy: 2015), pp. xviii-20.

[76] Laura Sullivan,, et al., Equitable Investments in the Next Generation: Designing Policies to Close the Racial Wealth Gap (Institute on Assets and Social Policy and CFED: 2016), pp. 9-11.

[77] William H. Frey, The The states Will Become "Minority White" in 2045, Census Projects (The Brookings Institution: Updated September 10, 2018).

[78] California Budget & Policy Eye analysis of Section of Finance data.

[79] This written report uses the terms "Asian" and "Asian American" depending on the cited source. For more on the SCF's racial and ethnic categories, see Lisa Dettling, et al., Recent Trends in Wealth-Property by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: September 27, 2017).

[80] Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, et al., The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles (Duke University, The New School, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development: March 2016), pp. nineteen-twenty.

gonzalezsheithers.blogspot.com

Source: https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/the-racial-wealth-gap/

Post a Comment for "Median Net Worth of White Families in California"